Changing the narrative of philanthropic investment in First Nations

“The act of fixing a problem, when done in the wrong way, adds fuel to a fire instead.” – Pro Bono Australia.

In 2019 Blak Impact Lead, Skye Trudgett was contacted by a philanthropic trust, that has chosen to remain anonymous, working in the First Nations space.

What did this philanthropist want with an evaluator you ask? You see, the Trust was taking a moment of reflection to consider alternative ways of working and to see where they could pursue more effective and more culturally appropriate approaches.

Current day and baring scars, The Trust is a systems thinker; addressing the concept of systemic complicity where they acknowledge that they are part of a system that is delivering outcomes that they can see is not just; The Trust knows that this ultimately means something they are doing (or are not doing) is contributing to that outcome.

Complex systems like philanthropy and First Nations can quickly become overwhelming. There are many moments where your focus can be on what other people are doing (or are not doing), and to think that change is not possible. For them, doing different looks like co-designing for impactful investing, stepping back to start tackling some of this decade’s challenges, being open about power and the liminal space between philanthropy and investees and to share their learnings with others for sustainability. And of course, capturing the impact, measuring the changes and reflecting on the learnings – this is where Blak Impact played a role.

Philanthropy and evaluation, white on white. To The Trust this was risky, yet if decolonised and Indigenised in the right way, this approach would be ground-breaking. And thus the implementation of genuine co-design began. Much of 2019 was spent engaging and recruiting Indigenous Critical Friends to hold The Trust to account, to co-design an Indigenised path forward and provide strategic advice over the next 10 years.

And amidst the uncertainty of COVID–19, Critical Friends and Blak Impact’s developmental evaluator met with The Trust to start the co-design. They explored what investing in the First Nations space actually means for First Nations peoples and communities, where that’s different to the assumptions held by the philanthropic sector and how we balance the two worlds we live in and seek to make change in.

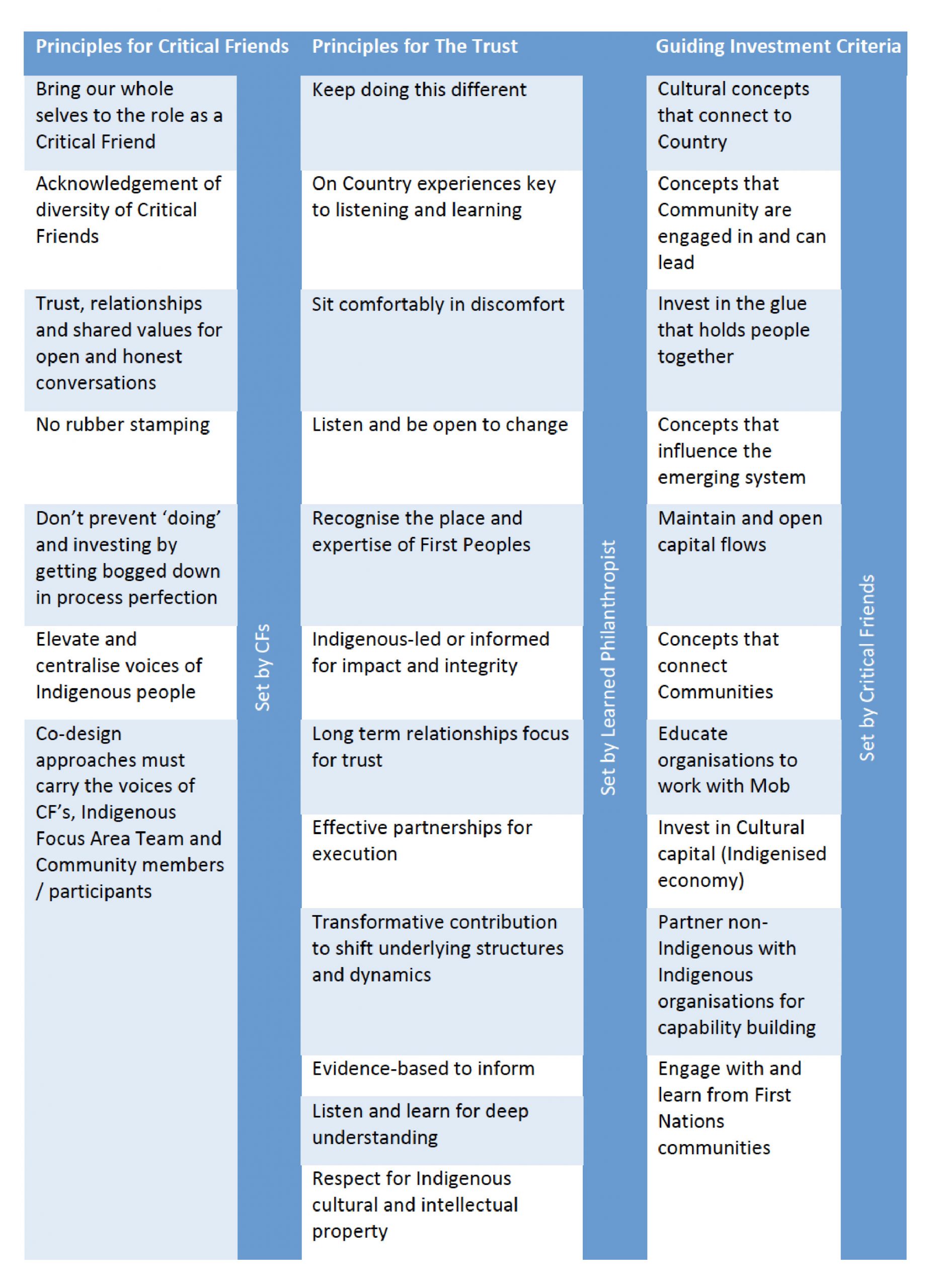

There are some core principles that emerged from this process:

Principles that arose from the co-design process

What we have done so far

It’s been an all hands in approach with The Trust and Critical Friends to develop some structural guides for moving forward, a theory of change and an Investment, Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (IMEL) strategy.

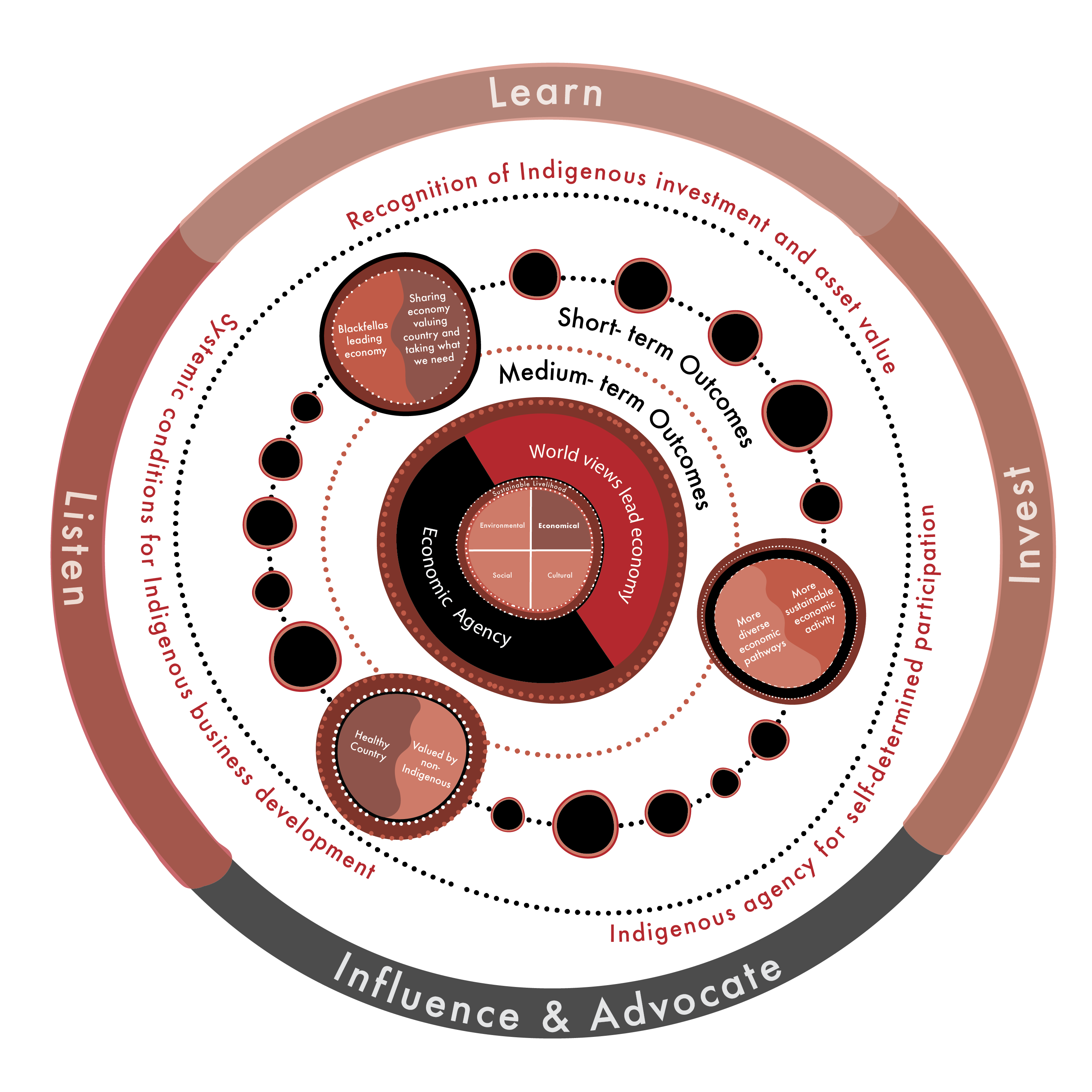

Theory of Change

We started the development of a ToC with Critical Friends by mapping their system, identifying domains of impact for creating sustainable livelihoods for First Nations and acknowledging that philanthropic investment focuses toward economic impact whereas investees apply holistic consideration to creating impact.

Interestingly, each investment will have its own ToC that is co-designed with investees and looks across the domains of livelihood sustainability that are relevant to them.

Sustainable Livelihoods for First Nations

Critical Friends sought to adopt a framework that balances domains that contribute to the sustainability of livelihoods for First Nations peoples, the framework has four equal components:

- Environmental factors

- Economic drivers

- Community need and focus

- Cultural systems

Philanthropy within the “whole”

The Trust has a critical focus on contributing toward change through an economic lens, leveraging the experience of Founders, board members and employees in this space.

This expertise however acknowledges that change toward the broader goal does in fact require the activation of all four components (or levers).

The Trust respects the wisdom of Critical Friends, Partners and experts across other components; and as such, a layer of complexity, co-design and emergent outcomes (that speaks to the whole) is incorporated into the broader theory of change.

Economic Justice: A just and inclusive Australian economy which assures dignity, equality and sustainable livelihoods for Australia’s First Peoples.

Investment phased monitoring, evaluation, and learning (IMEL)

Throughout the co-design, it became quickly evident that a comprehensive and flexible approach was required for IMEL, capturing the “whole” and allowing for flexible co-design approaches with current and new investees. The IMEL strategy equipped The Trust and their investees with a tool to conduct phased monitoring, evaluation and learning activities in an aligned and integrated manner; and across all investments. To do this, there are 2 IMEL strategies:

- One for the Trust, building their readiness for this work and holding themselves to account. This strategy has moments where it leans into what is happening on the ground where it invests.

- The other is co-designed with investees, building their readiness for measuring impact and pivoting based on evidence and learnings.

What we have learned along the way

Post the structural development of this work, we sit with many take homes ahead of implementation:

Focus on outcomes and impact, not activities or inputs. Evaluation should support better decision-making by both the implementors and funders, not just a story

When you start to scratch the surface of philanthropy in First Nations, you come to see that there is too often a significant divide in world views between philanthropists and investees; or it’s a “nice thing to do” that doesn’t warrant nor demand a rigorous approach to measuring what really matters to both parties. The Trust sought First Nations thinking to balance the need for impact measurement that leverages Traditional scientific methodologies to understanding impact and responds to the Western paradigm of “rigorous enough” impact measurement.

Measure success as defined by the community. Start by understanding what the goals are and set your outcomes/impact against this

Sir Ronald Cohen has recently stated that philanthropy needs to shift from funding activities to funding outcomes, and whilst we agree with this in principle, again, the question remains, whose outcomes; and are philanthropists ready to acknowledge that perhaps their outcomes don’t really matter on the ground? The “outcomes” must be self-determined by Community when investing in First Nations communities, organisations and initiatives. It is this understanding that led us to developing flexible theories of change and IMEL strategies.

Fund what is needed, not what you (the funder) wants. Contribute thinking, knowledge, share in the success and the failure – this is co-design

Co-design, it’s the new buzz word floating around but what does it mean? In our view, “co” is not a participatory workshop, it’s a culture of centring First Nations peoples’ priorities and needs. It’s a negotiation with philanthropy. Grace O’Hara speaks of the need to listen deeply, talk to First Nations peoples with lived experience, hear their challenges and needs; we will share them.

To do this, you may need to change yourself first. First Nations peoples do not need to change to partner in co-design; it is Philanthropy who must change mindsets and methods. People with less power shouldn’t have to make themselves heard; people with more power must create more safety, generosity and hospitality.

Be brave, if no one else is funding something, understand what it looks like for your organisation to be a “lead funder”

Rachel Kerry from CAGES Foundation has provided solid advice for philanthropy to “be prepared to feel uncomfortable, have a long-term view and don’t assume you know what success looks like for communities. Be respectful – ask and LISTEN!” The CAGES Foundation has, for several years, followed this approach that is dedicated to building trust within communities and allowing Indigenous voices to be heard throughout the grantmaking process – but what happens if no one else is funding the things that you heard as being critical to Community? Be brave – sit in your discomfort and the sanctity of sharing risk with others in power, cede power and give way to First Nations agency. Furthermore, become a “lead funder”, advocate for your investee, mobilise others to follow your lead.

The role of a funder can and should extend beyond just funding.

The Trust took a step back to understand their role as a powerful player and with value to offer organisations who are seeking to walk in two worlds. The Trust acknowledged that First Nations peoples are often expected to walk in two worlds, and thus the novel approach for The Trust is in fact proposing the same for philanthropists. There is significant value in creating a safe space where philanthropists can support readiness of First Nations organisations to use language that speaks to potential funders and can increase success in channelling capital and consolidating reporting. Philanthropists should use their view of the system and various models of change to provide advice, consultation when and if desired by the partner, including during scoping phase.

Overall, The Trust has some key actions for others who wish to commit capital to the First Nations sector, in a way that is truly co-designed and measures impact beyond the “nice story”:

- Co-determining what to focus on, alongside First Nations peoples

- Changing ourselves first, as individual and organisations (in particular, our mindsets and decision-making processes)

- Resourcing co-design, including the labour of First Nations peoples and the outputs of co-design

- Building trust to enable the meaningful sharing of lived experience

- Avoiding planning paralysis and perpetual discovery – getting to implementation

- Defining what is to be measured and measuring it, with people

By Blak Impact and Anonymous Trust